Slopeside Nostalgia

I watch a whole world slide by, children zooming past wobbling adult beginners. Au final, il se trouve que le monde est assez petit. (Originally published on my website in March 2024.)

I watch a whole world slide by from inside le Teide. To most, this cafe in the base lodge of La Pierre St. Martin wouldn’t stick out from any other restaurant at the ski resort. The popcorn ceilings are reminiscent of topographical maps of these mountains, les Pyrénées. The specials are written on a blackboard and the sparse decor consists of vintage Coca-Cola advertisements, red paper stars, red paper place settings. The sun shines blindingly through the windows. Small children zoom past wobbling adult beginners. The snow slowly melts and the pic d’Arlas rises above it all against a bluebird sky.

My grandmother used to sit at one of these heavy wood tables all day and buy us a treat after our lessons. Merci Mamie. Half of the appeal of skiing is the end of the day. You take your boots off. We’d order des crêpes nutella avec un chocolat chaud. Et qu’est-ce qu’on dit ? S’il vous plait !

Adulte, I’m more partial to a crêpe citron. I place my order, s’il vous plaît, and wait.

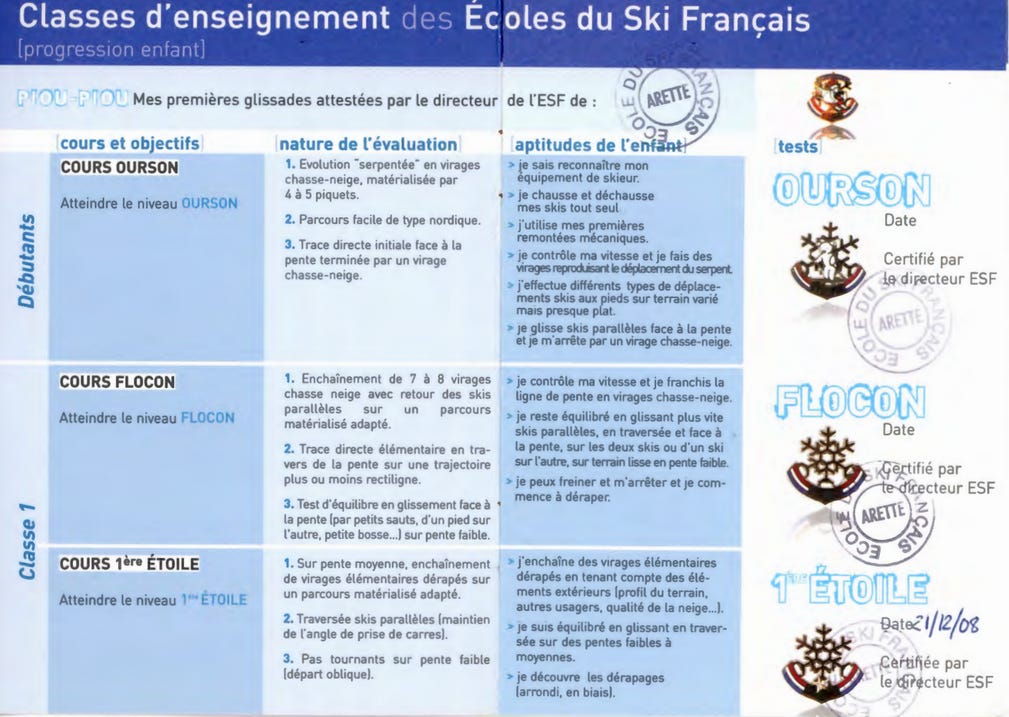

Meredith, Naomi, and Sari are learning how to ski this weekend. Booking a lesson for my friends, suddenly I become my father all those years ago booking a lesson for my brother Eliot and me. Buying us the première etoile badge, because we were proud of ourselves and he must have been proud of us too. He’d give us the pins and tell us to be careful, to not lose them. We’d attach them to our sweaters—“Make sure they’re visible!”—and he’d take our photo.

Some ski instructors, ski patrollers, and staff are regulars at Le Teide. They swagger in their ski boots and greet everyone behind the bar, then go straight into the kitchen; there, a six-feet-tall Santa Claus look-alike is having lunch. His tan is almost orange and clashes gloriously with his red jacket and snow-white hair. I recognized him immediately.

We waited for the girls’ ski instructor beside the ski school. Cherchez le père Noël, they had told us. Serge walked up and I was ten years old again—I’m absolutely sure I took lessons with him a dozen years ago. Has he spent every winter here since, having lunch in the Le Teide kitchen? And how many winters before?

“When did you start?” That’s common ski lift small talk. I find myself shocked sometimes at the answers: five, three, two years old. Serge tells Meredith that he’s been skiing since he was seventeen months. I guess some people see their kids just starting to walk and think, Great, time to strap sticks to their feet and throw them down a mountain!

I’ve been skiing for eighteen years. It was December 2006 and my parents had just bought a house in France. When Eliot and I were small our family vacations were spent driving all across l'Hexagone, visiting family. Now here was one place, ours, in the mountains of my dad’s childhood: there they were, covered in snow, when we went for Christmas.

I was 8. My brother was 6. Our first encounters with moniteurs de ski were nervous. We had rarely spoken French to strangers. I did figure skating at Lasker Rink in New York on Friday evenings, and I asked the moniteur whether skiing was similar. Les mouvements se ressemblent un peu, he said, mais il ne faut pas trop patiner. Meredith asks Serge a similar question. Dans le ski, he reassures her, on sait qu’on ne tombera ni en avant, ni en arrière. Les skis nous stabilisent.

It’s a 45-minute winding drive back to our house from La Pierre. From the main road, you take a right at the church, a left at the apricot tree, another left at the old spring, and pull in to a driveway with tall piles of firewood. The facade of the house turns shyly into the crook of a hill. Down in the village you can only see the house in wintertime, peeking out from between leaf-naked branches. The tattle-tale chimney smokes into the sky.

Our garden is encircled by trees that press in on the house. Soon after moving in, we felled an ancient pine, too old and too close to the house for comfort. The wind is strong and a tree falls every storm, so my mom told us when men came to climb and cut up the tree piece by piece. It seemed sad to me in daylight but at night I dreamed of branches crashing in through the roof. What a strange place for a New York City kid to land, used to dreaming well above the treetops on the ninth floor of an apartment building. It was home and it was so far away from home.

Around this time of year the house always smells like wood smoke. Eliot and I would roast marshmallows and chestnuts over the open fire. With a vestigal door to the old bread oven and a chain from which to hang a cauldron, it seemed ripped from a storybook. We sat on the züzülü, a traditional Basque bench, playing Scrabble and reading. Not so long ago, so my parents told us, people slept on this bench by the fire to keep warm. Over these vacations I’d Facebook message my friends in the United States, barely able to spell out these stories in our shared language. It seemed they’d have to see it for themselves to understand, but it’s a long haul from the Upper West Side.

We always sit around the fire after a day of skiing. Here, I am eight years old charting the similarities between figure skating and skiing, the vast differences between teaching styles in France and the United States. I am twenty-five, telling Meredith, Naomi, and Sari they’ve skied brilliantly and tomorrow will be even better. Sari had never seen so much snow growing up in Colombia. Meredith grew up in snowy Massachussets but had never skied either. They all sit on the züzülü and Naomi plays guitar. What a strange place for us all to land.

The house is a four hour train ride from Paris and an hour’s drive through twisty roads from the station. We left work early on a Friday afternoon and walked to Montparnasse. They play music in the car and we chatter away in a mix of English and French as road signs flash past in Basque. Au final, il se trouve que le monde est assez petit.

La Pierre is a small resort. I can picture the whole map in my head. But from the highest point is an incomparable panoramic view, only a few hundred meters from where contrabandiers would cross over from Spain. On my favorite run, the Boulevard des Pyrénées, it feels like you’re skiing straight down into the valley from the sky. These gaps might be getting smaller.

I’m halfway through my crêpe citron when Meredith, Naomi, and Sari walk back in to Le Teide. They’re back from their first lesson with Serge with wind-swept hair and sparkling eyes. They order chocolat chaud and tell me about who fell, and how many times, and I wish I could buy them étoile pins and take a picture.

We go back to the ski school to sign them up for the next day.

“Did you want to go with Serge again?” his colleague asks.

“Of course, if he’s free!”

They detect an accent in someone’s voice.

“What brought you to La Pierre St. Martin?”

What a strange place in which to land!

“That’s my doing,” I reply. “My parents live nearby, and I learned to ski here. D’ailleurs je trouve cette question bizarre. Pourquoi La Pierre St. Martin? C’est la meilleure station de ski du monde

Nota Bene

A couple of recommendations

Atelier, the new podcast from Columbia Global Centers | Paris ;)

The "History of Ideas" series of the podcast Past, Present, Future

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

Transformations by Anne Sexton

Bluebeard's Egg by Margaret Atwood