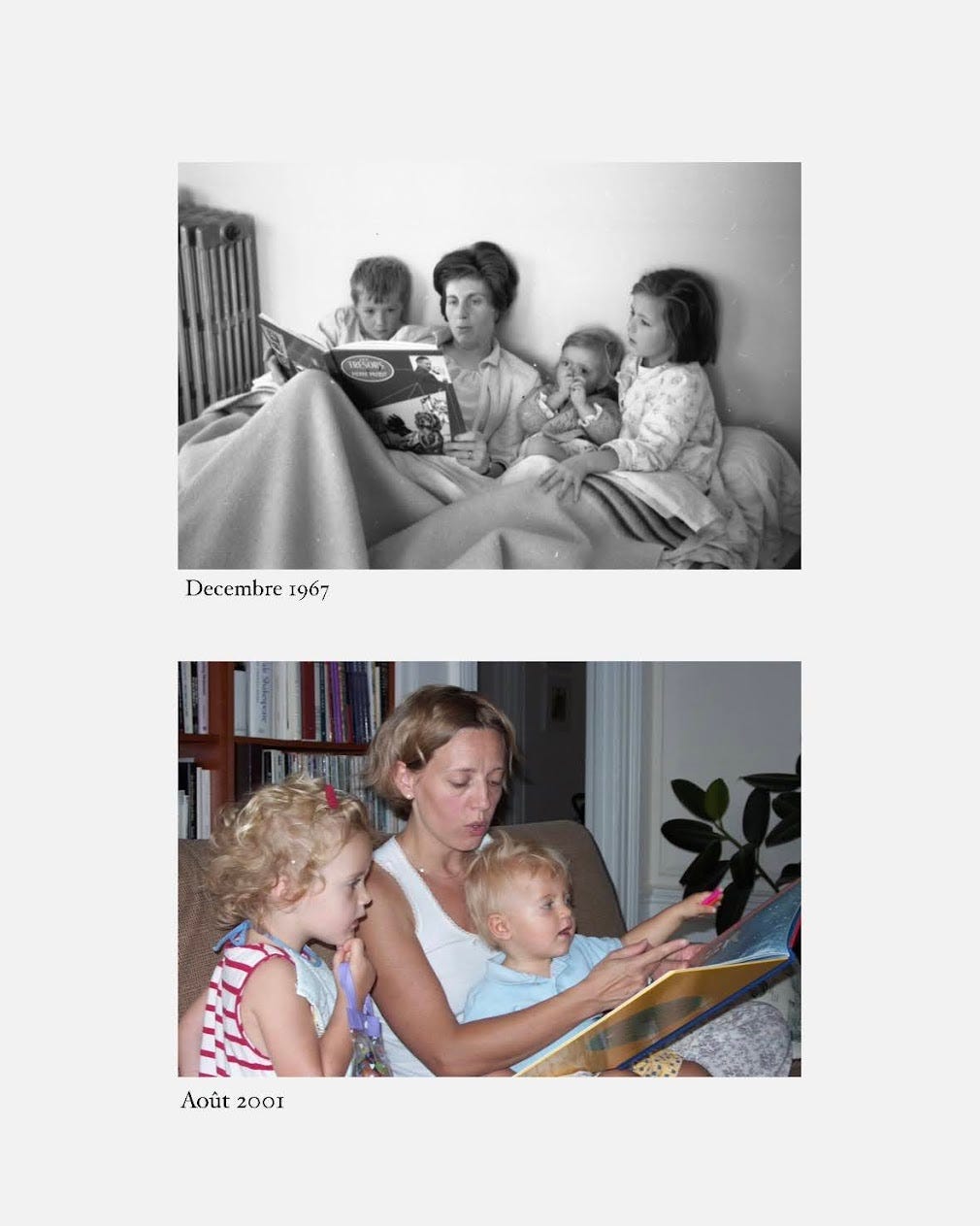

The first reading I’ve done for my master’s has sent me on a Saturday evening spin into contemplations about families, photos, memory, and ghosts. I’m reading Photos de familles by Anne-Marie Garat (Actes Sud 2011; Seuil 1994), in which she examines the concept of family photos and photo albums and spins tales about anonymous photos she has collected over the years.1

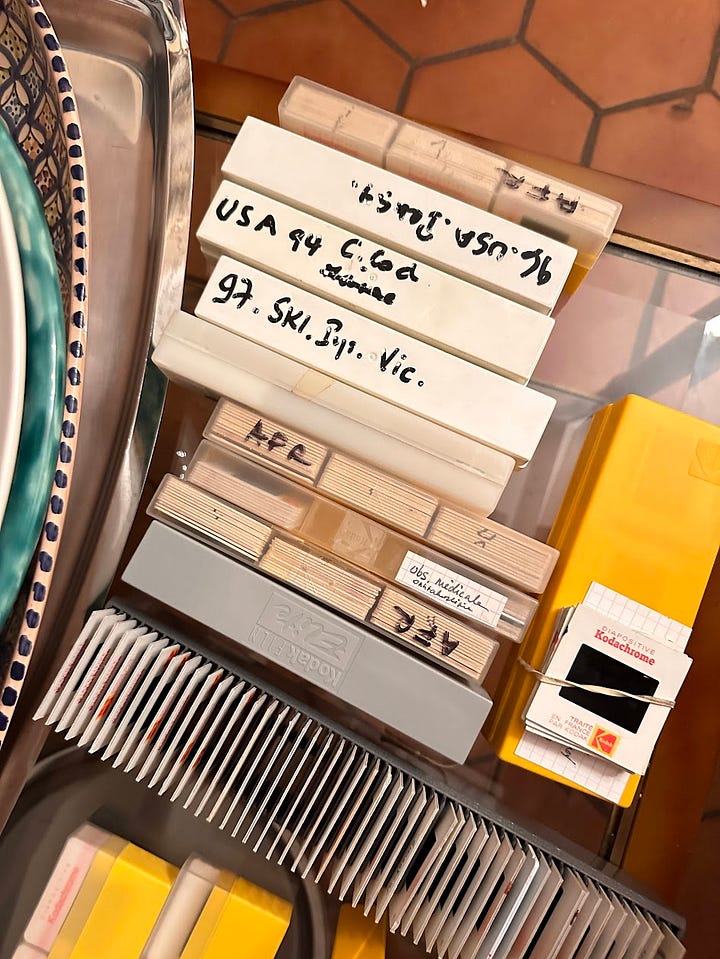

Whenever my dad visits his parents in Toulon he brings a high-res scanner and spends hours in the dimly-lit living room digitizing film and diapos. He sends a periodic Dropbox folder to our extended family email chain, which includes cousins and second cousins, and is named after my great grandparents. Our family photos, unlike Garat’s collection, are not yet anonymous, although the randomized numbers on the scan files do not correspond with a time or date, and the photographs don’t have a digital impression indicating time and place.

In my personal photo albums on Google Photos, I can search by date, holiday, address; I can even search by face; or put in a term like “cat” or “book” and some algorithm will neatly sort out the photographic evidence of my life into little digital piles for me to scroll through. My own Instagram account(s) are like a photo album of my life and I wonder, as I read Garat, what she would make of these digital albums. Her book was written in the late 90s, and alludes to cheapened quality of photo albums and the onset of digital photography, but does not conceive of a paperless world of photographs. I’m not sure I fully “conceive” it either, but I feel compelled by the idea of tactile photo albums that haunt houses, physically almost-present and belonging to a family like a Roman lares. Dropbox folders are less easily picked up, brushed off, and pored over after family dinner. Sometimes my dad has taken out a TV or projector to screen newly scanned photos. At the end of my trip this summer, I sent my grandparents photos and gave them a commented presentation of my trip as I flipped through the photos on TV. Sometimes I sent photos to you on scribbles. These are gestures at sharing better.

It’s easy to think that we capture a moment in a photograph, and yet, photos often mean nothing without (con)text. A random photo portrait at a flea market is nothing, and yet, might have meant everything to the people who loved its unnamed subject. The little printed papers float about in stacks of 100 others like it, unlabeled with names, because the people who took them didn’t need to write the name down to remember them.

Garat talks about the omissions in photo albums, too. The periods in which we take no photos, the people behind the camera, the photos simply left or taken out. A digital photo album is the same. My Instagram is a form of photo album and yet rarely shows me, only slightly shows the people I love. (I post things I find beautiful or interesting. When I look at my dad’s photos from his youth I see he took the same sorts of photos, and very few of himself, and I am frustrated! I should probably take more photos of myself.)

I don’t miss the age of Facebook photo albums with 100 flash-photos of one middle school hangout, either. Maybe the implied voyeurism and lack of context on social media make the sharing fundamentally dissatisfying. Will I write a caption for each photo in the same way my dad might tell me about his parents when showing me new photo scans?

My dad informs me that Garat is a Basque surname and that we have a not-so distant relative with the name!