In January I read and watched and did things! This article will be interesting to you, of course, because I am the first person ever to write about things I have read and watched and done. Despite the enticing novelty of this proposition, if you require orienting to decide whether to read further, here is a brief overview. (Click the links to scroll down the article!)

I read Small Things Like These by Clare Keegan and Permafrost by Eva Baltasar (trans. Julia Sanches). I watched Bye Bye Tiberias (2023), The Outrun (2024), Babygirl (2024), and Anora (2024). I saw a retrospective of Colombian textile artist Olga De Amaral at the Fondation Cartier, and iconic Ukrainian band DakhaBrakha in concert. I also scribbled at length elsewhere about the Marxist subtext of Knives Out (2019), the precarious beauty of European minority languages and Kneecap (2024), and Virginia Woolf’s uses of photography in Orlando.

Reading

Small Things Like These

by Claire Keegan (2021)

Before long, he caught a hold of himself and concluded that nothing ever did happen again; to each was given days and chances which wouldn’t come back around. And wasn’t it sweet to be where you were and let it remind you of the past for once, despite the upset, instead of always looking on into the mechanics of the days and the trouble ahead, which might never come.

A few key phrases to entice you

Preparing for Christmas in a small Irish town in the 1980s

Sensitive narrator contemplates people and objects from a dissociated distance, when suddenly, moments of emotional clarity and action spark forth

Evils of the Catholic church on blast

A brief review (with light spoilers)

I should start by saying that I have been telling most everyone I know to read this book. If I know you and I haven’t told you to read it yet, this is me telling you!

Hilary Mantel, quoted on the front cover, said: “Wastes not a word.” This really is a shining quality of this novel—really, short enough to qualify as a novella—whose brilliant economy of words sparkles like light off of a perfectly cut gemstone.

Bill Furlong’s is a self-consciously precarious cozy world—dubbed a “snowglobe” in several reviews—tensely adjacent to the not-so-distant condemnable history of Ireland’s Magdalen laundries. These were run by Roman Catholic orders from the 18th to late 20th centuries. The last closed in 1996. Ostensibly designed to house “fallen” women, approximately 30,000* were imprisoned, and thousands their children perished. *It is not known exactly how many women were affected because many records were lost or destroyed.

Most of Furlong’s life —from the numb routine of his thankless work to his childhood with a single mother—seems a dissatisfied, confused fog. Everything seems, or might be, or could have been. And then, he feels a crystal clear impulse, that of moral clarity, which sweeps over him almost like an external force, or maybe, like his “self” triumphing over other concerns.

The story almost resembles a modern fable, about how any of us can and should react with whatever small power we have to resist injustice.

You can read it in one sitting. It’s so short and so perfectly constructed, that you’ll pick it up and put it down and realize that the window is still open but it’s gotten cold, and it didn’t matter, because you just read something perfect.

Permafrost

by Eva Baltasar, translated by Julia Sanches (2018)

t.w. This book heavily features suicide/suicidal ideation. I should add that I found it oddly life-affirming for a book that spends so much time with death, though maybe that’s not so odd after all.

Something inside her was burnishing every single thing she did, every measured word she said—but who? Catalan phrases strutted out of her throat wrapped in French-accented mink, but with a lowly, port-like fragrance that I attributed to her Marseilles roots and which drove me wild. In her mouth, Catalan sounded the way it should sound as a perfect language. Any word I said immediately afterward was a faded daisy in comparison, a silly little flower. I’ve never spoken as sparingly as I did with her, and I’ve never enjoyed the lead-in to a conversation quite as much.

A few key phrases to entice you

A book about a woman who just wants to be left alone to read

Every lesbian narrative I’ve read lately confirms I’ve never had an original experience. (Is this what straight people feel like every time they read?)

The narrator is frosty and difficult and her voice is so funny I was laughing throughout, until I sobbed.

A brief review (with no spoilers)

The first thing I heard about this book is that it was beautifully written—that Baltasar had published over a dozen poetry collections before this novel. And then I read the first line of the blurb: “Permafrost’s no-bullshit lesbian narrator…” Sold.

The qualifier “no-bullshit” probably alludes to how Baltasar fearlessly treats taboos, from lesbian sex to suicidal ideation. The brief, pages-long chapters (sometimes no more than vignettes) glide from childhood through early adulthood and a slippery sense of present day, evoking both the emotional “permafrost” of the narrator and the conditions in which it came to be. But as the narrator describes in detail in a middle chapter, she is constantly bullshitting: “I have something I need to say: I am not a sincere person. No, I’m someone who lies.”

No meta-textual interlocutor is ever introduced, and so the narrator seems to be addressing the reader directly. Given the narrator’s prickly misanthropy—the distance that she creates between herself and everyone around her, and especially with their expectations of her—the confessional narration and the act of writing all of this itself is striking. This is why I refer to a slippery sense of present day: it seems that the narrator has cut off the story at a given point, but is writing from further along. And indeed, two books follow, which I can’t wait to read.

About the translation

As I make a point to read more books in translation, especially from contemporary authors, two publishers keep cropping up: And Other Stories and éditions Zulma—translating to English and French, respectively, though both also publish books in their first language, too! I have a few books from Zulma and finished my first last year, Du Givre sur les épaules, translated from Spanish, one of thirty languages from 45 countries represented in their catalog. Last year I also read my first book from And Other Stories, Verdigris, a highlight from 2024 that I wrote about in a previous scribble. I decided to start this year with a translation from a new language, Catalan, with Permafrost.

The translator Julia Sanches writes a beautiful afterword about the process of translating Baltasar, in which she opens to contemplation of the practice of translation itself, which she likens to “craft.”

Would translation be quite so controversial if we were to simply call it something else? Would people still enter a translated text with as much suspicion if we called our little art something like "versioning" or "againing"?

I would love to be able to understand the original Catalan in order to better understand the way in which Sanches rendered the poetic stress of Baltasar’s prose; apparently, the only stipulation given by the author. In a given phrase, the musicality and rhythm had to be conserved in priority, over for instance the semantic meaning of a word.

Sanches also addresses the choice to translate the Catalan word “cony” as “cunt,” a recurring word throughout a text where lesbian sex and desire are central. There is no perfect translation into English, she writes, because the Catalan word is more neutral, without the vulgarity of the the chosen English translation. The alternative, “pussy,” was set aside because the translation was done in 2020 near the end of Donald Trump’s first presidency: “I can’t help thinking of that time he said ‘pussy’ and still won the election.” I have often thought that the vulgarity of these words seems so far removed from what they actually denote; really a blind spot in the English language where I feel there is no good word to use. I was glad Sanches addressed this translation choice, and chose to re-situate the English word in a Catalan context, almost reclaiming it: “I have striven to make it as much of a non-issue as desire is in Permafrost.”

Watching

Bye Bye Tiberias

dir. Lina Soualem (2023)

Watching Bye Bye Tiberias in January 2025, on the 13th day of this year’s ceasefire, was a strange experience when the film itself was made before October 7, 2023. The film traces the lives of four generations of women in filmmaker Lina Soualem’s family—from her great-grandmother, Um Ali, who was expelled from Tiberias in 1948, to Soualem herself, the French-born daughter of a Palestinian mother who left home.

At the heart of the film is Lina’s mother, actress Hiam Abbass, who serves both as a storyteller and as a performer reenacting pivotal moments from her youth—arguing for a place at a photography school in Haifa, telling her father she would marry an Englishman. Abbass’ awareness of the camera contrasts sharply with her mother Neemat’s unselfconscious presence. Their interactions were, to me, the film’s most heartbreaking moments, as they confronted the emotional weight of physical distance (from Galilee to Paris), Abbass’ decision to leave, and, ultimately, Neemat’s death and the family’s mourning.

During the Q&A, an audience member asked about a particularly moving scene: Um Ali’s husband, devastated by the loss of his farm, wanders the countryside asking, “Have you seen my cow? Have you seen my donkey?” Reading a version of the anecdote written by her daughter, Abbass adds, “Have you seen my life?” In the film, Soualem asks her mother: How do I live as the granddaughter of people who lost everything? The question remains unanswered when the credits roll, and the audience member wanted to hear her response. Soualem admitted she might never find a concrete answer—that generational trauma is something one never fully sheds. But she shared a metaphor her mother used to explain how to bear it: If you have a ladder to carry, you could hold it horizontally, but you’ll keep knocking it into things. If you raise it vertically, you will still have a ladder to carry—but you’ll be able to move forward. Making films, Soualem suggested, is one way of keeping the ladder upright.

I watched Bye Bye Tiberias at work, during an event titled “Artmaking in Crisis,” organized in honor of Palestinian poet Doha Kahlout, a displaced artist-in-residence at Reid Hall this year, though currently stranded in Gaza. The event brought together a network of artists supporting her in Paris, opening with a performance by Palestinian singer-songwriter Bashar Murad. Novelist Karim Kattan read from his latest book, L’Eden à l’aube, and we screened a pre-recorded video featured Doha reading her poetry, translated by Yasmine Haj. The video also included young female students from Gaza reading their own poems.

The Outrun

dir. Nora Fingscheidt (2024)

Spanning across London and several isolated islands in Orkney, in the north of Scotland, The Outrun unfolds in a nonlinear manner, marked by the changing colors of Rona’s hair dye. Her blue hair doesn’t stand out in a London nightclub, but it starkly contrasts in Orkney, where she is often alone, and always lonely.

Rona has returned home after her alcoholism caused a breakup and led her to drop out of school. Her relationship with herself and others improves as she becomes more attuned to the elements around her on the especially isolated island of Papay in Orkney. She has an almost magical relationship with the weather, often imagining she can control the wind and rain, moving her hands or arms in a dance. While she suppresses this in London, in Orkney, the extremes of nature allow her to be in concert with the extremes within herself—her deep pain and passions, frustrations and fascination—which no longer seem as frightening when experienced alongside titanic winds and bonfires.

Because the film was shot on location, the Orcadian weather becomes almost its own character. The shooting schedule included four trips: to film lambing in April, birds nesting in June, principal shooting in September when the seals approach the coast, and winter scenes with the snow. Ronan did the lambing herself, supervised with a local farmer, and often swam in the cold sea during filming. A moving scene of seal song was not created in post—the very real seals spontaneously reacted to Ronan’s actual singing. Although the story on the surface is about recovery, I fell in love with The Outrun because it’s the story of a relationship between a woman and the natural world.

Rona gets a job at a natural preservation organization tracking corncrakes, a local species of bird. “We hear them before we see them,” her coworkers say. Indeed, she spends many sleepless nights recording the sounds of the Orkney countryside, never hearing a single corncrake—until the very end, an incredible moment of catharsis after Rona has spent a year on isolated Papay, studying seaweed and swimming with seals. Birdsong has never made me tear up so quickly.

Anora

dir. Sean Baker (2024)

I was a latecomer to the Sean Baker cinematic universe, arriving when Red Rocket hit theaters. I later googled him and discovered that sex work is one of the principal themes in his films. When Anora was announced, I was excited to see the next entry in his catalog, though a bit apprehensive. While I enjoyed Red Rocket, I also found it extremely difficult to watch because the main character is essentially deplorable. Anora was much more watchable, perhaps because the power dynamics are so different. In Red Rocket, Mikey "Saber" Davies is a washed-up pornstar trying to make ends meet after returning to his hometown. The only resource he seems to have is manipulating women: his estranged wife Lexi, with whom he moves back in, and a teenage girl nicknamed Strawberry, whom he believes will be his ticket back into the porn industry as a double act. When his web of lies tightens around him, I thought, "Good riddance"… and yet, the reckoning is bittersweet.

Anora was a totally different moviegoing experience: it was not difficult to root for the main character from title to credits. Anora, who goes by Ani, is a determined and hardworking stripper at a high-end Manhattan club, living in a poor Russian neighborhood of Brooklyn. She works all night, takes a long commute home, and sleeps in a bedroom pressed against subway tracks. Then she meets Ivan, who goes by Vanya, the son of a Russian oligarch. Initially, Vanya seems to be her ticket out. When he asks to hire her full-time while he's in the US, and later marries her in Vegas to stay, it seems like a Cinderella story to Ani and her friends. But then reality sets in.

Of course, it’s not a Cinderella story, as Ani doesn’t get the happy ending she expected. (That said, I’m pretty sure being the wife of a Russian oligarch would be a happy ending, even if it’s more materially comfortable than emotionally fulfilling.) The entire story is a whirlwind of Ani fighting tooth and nail to make the best of the situation—to survive. She seduces Vanya, navigates his childish whims and sexual inexperience, molds herself into a simplistic image of a “wife” for him, helps the cronies find him during a sleepless night, and dares to introduce herself to Vanya’s terrifying mother, who threatens to destroy her. Ani fights the entire time, from beating up professional henchmen to insulting Vanya in front of his family (to his father’s great amusement). Only at the end does she break down, showing the strain of this whirlwind “romance,” when she realizes that the henchman Ivan has shown her a very small gesture of humanity.

Overall, the film is very enjoyable, with a good pace and excellent performances, though none of the characters are particularly fleshed out as individuals. Just because Ani works all night doesn’t mean she wouldn’t have friends, hobbies, or aspirations beyond making more money! This makes them more like social class symbols than fully developed people. “Cinderella” doesn’t get her happy ending, but the film still functions a bit like a fairy tale in this way. Despite the disappointment that Ani isn’t more fleshed out, I actually find this quite compelling.

Inspired by Anora and its relation to Cinderella, I wrote this short piece for the third edition of Les Cassettes, borrowing some of the film’s aesthetics—though I swapped out the oligarch’s son for a DJ. Indeed, in a contemporary context, what would it look like for a woman to meet a “prince” at a “ball”? And what does it mean to be “saved”?

Babygirl

dir. Halina Reijn (2024)

My overwhelming feeling after leaving the theater was a desire for better storytelling about women’s sexuality and desires. Anora and Babygirl both lack character specificity, but while Anora has a fable-like quality that makes this more effective, the characters in Babygirl feel more like vessels for emotions pre-selected for display. The relationship between Romy and Samuel felt more like the expression of a pre-determined dynamic, than the natural result of chemistry between two specific people. In a story like this, with its professed social and political vocation, that felt like a missed opportunity. Ultimately, desire doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and it can’t be distilled into a formulaic story. Desire is specific, strange, and complicated, and a story that focused more on its characters might have conveyed this better.

The most compelling aspect of the movie for me were the almost-elided moments where Romy refers to her “fucked-up” childhood in cults, her wellness treatments and therapies, the flashing clips of childhood that haunt her. These moments are dangled before the viewer as the explanation for her difficulty expressing her sexual desires. This seems to be the crux of the story, but it’s given almost no screentime, taking a backseat so we can watch Romy and Samuel stare at each other from across different rooms.

Meanwhile, Samuel is an almost fae-like creature, supernaturally attuned to people’s needs. In one of his few humanizing, vulnerable moments, he admits that his ability to sense what others need scares even him. But there’s no follow-through on this.

Babygirl is skilled at evoking sexual tension—including its levity, the awkward moments where Romy and Samuel clearly have no idea what they’re doing, the shame and guilt of the affair and their workplace relationship. Yes, this is well done. But the film never gives them any real substance or specificity.

While Romy begins to unpack and accept her desires during her affair with Samuel, the film’s finale seems to imply more of a resolution and salvation for her family unit and marriage than a true acceptance of her sexual desires. If she returns to her husband, why do we never see a scene where they have an authentic, vulnerable conversation about what it is that she wants? Isn’t that the whole point?

The parts of the movie I liked were so brief that they were frustrating. I’d love to see more stories like this—not just more movies in number, but movies with more to them.

Outings

Olga de Amaral

at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain

Website | Open through March 16, 2025

This is the last exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in the 14th arrondissement, before they move to their new building on rue de Rivoli!

“I live color. I know it’s an unconscious language, and I understand it. Color is like a friend, it accompanies me.” — Olga de Amaral

I was fortunate to visit the exhibition with work, guided by the French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh, who designed the exhibition space.

On the ground floor of the Fondation Cartier, Olga de Amaral’s large-scale textile works reflect and refract the light of Jean Nouvel’s glass walls, mirroring the organic textures of Lothar Baumgarten’s garden. To one side, large tapestries hang to create smaller rooms and corridors. To the other, textile “mists” from Amaral’s Brumas series hang from the ceiling, catching the sunlight by day and reflecting in the windows by night.

Downstairs, in the basement, Amaral’s gilded works glow like a treasure cave arranged around a spiral. The dark paint in these downstairs rooms transitions from reddish taupe to dark blue, evoking the shift from the walls of a cave to the expanse of the night sky. Ghotmeh showed us how the roundedness of the walls is emphasized by a scraped texture, achieved by a single artisan. These lines on the walls are echoed by a lighting design on the floor, creating a spiral shape that mirrors the design on one of Amaral’s tapestries.

In the last room, Amaral’s Estelas are suspended like golden megaliths—I thought of Rosemary Hill’s recent article in LRB about stone circles. Estelas means "wake" in Spanish, like the trail left by shooting stars, but it also refers to a "stele,” or tombstone. One side is defined as “daytime,” where the golden face of the Estelas shines, and the other as “nighttime,” where the shadows of the works criss-cross and the light is reflected on the blue wall, making look even more like the night sky. A crescent-shaped bench along each wall invites visitors to contemplate the works; it’s the only seating in the exhibit, as if inviting reflection on everything seen in this dark, calm space before exiting.

Born in 1932 in Bogotá, Olga de Amaral is an emblematic figure of the Colombian art scene. In the 1960s and 1970s, Amaral contributed to the development of Fiber Art, drawing equally from Modernist principles and the folk traditions of her native country. Her work can be found in major public and private collections worldwide, including those of the Tate Modern, the MoMA, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2021, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, dedicated a major exhibition to her entitled To Weave a Rock. This exhibition is Amaral’s first major retrospective in Europe.

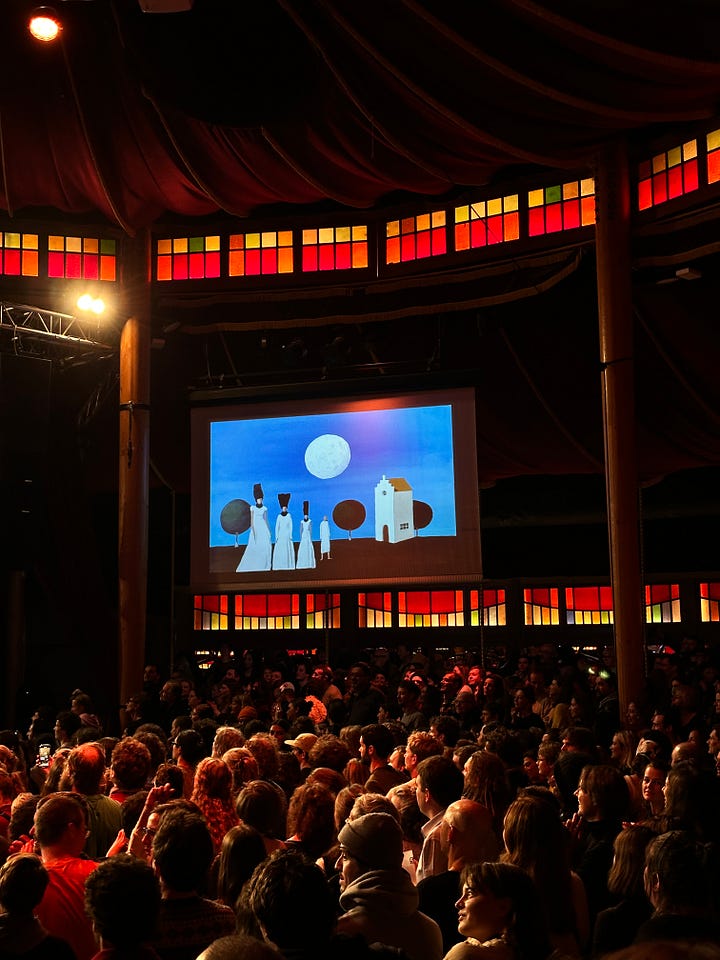

DakhaBrakha

in concert at the Cabaret Sauvage

The band name DakhaBrakha means “give/take” in Ukrainian, which seems fitting for their blended music style, self-described as “ethno chaos.” At their concert in January, I discovered the Ukrainian folk influences I expected, as well as elements borrowed from styles ranging from rap to techno, all blended together with truly incredible instrumentation and harmonies. They even mimicked birdsong—I had heard a recording of that track on Spotify but had no idea these were sounds they made themselves.

I was especially intrigued by one song, Karpatskyi Rep, or “Carpathian Rap.” Cellist Nina Garenetska introduced it as a song about a doomed love story set in the Carpathian mountains, which is apparently a bit of a trope in Ukrainian culture… The only other reference I have for a Carpathian love story is the film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, which is certainly not a happy one.

You can watch a live performance of the song here:

I’ve learned since that DakhaBrakha writes some songs, including this one, based on stories collected from villages throughout Ukraine. Garenetska recorded this particular story about a young woman in a small village looking for a husband. While searching, she goes through many men, each of whom has a problem: a bad mother, no house, a crooked nose. Upon looking more closely, the lyrics and story are also so contemporary—it made perfect sense here to meld traditional style with rap.

Here’s a translation I found of some of the lyrics:

“If only my Mom knew

What Vasyl is capable of

She would just tell me

”Oh my God, no way!”

A cuckoo was calling

Somewhere over there

Where all the guys are good

But Mykola is the best.

A cuckoo was calling

Over there near the forest.

I don’t love anyone

Like that Yurchik guy.”

Poor guys… Maybe this girl needed a wife instead!

![My Letterboxd review: have you seen my cow? hav you seen my donkey? have you seen my life? [watched at reid hall on the 13th day of the 2025 ceasefire] My Letterboxd review: have you seen my cow? hav you seen my donkey? have you seen my life? [watched at reid hall on the 13th day of the 2025 ceasefire]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Lee9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff3e2ab4b-4ee7-462b-8660-80f39be8be45_954x241.png)