Tin Ornaments

In which I decorate for Christmas, mull over the history of tin ornaments, and share printable templates.

This year, Christmas spirit has descended upon me like the ghosts of holidays past, present, and future. A decorative fervor has accompanied it, and I have spent many evenings over the past weeks crafting decorations for my little studio apartment. With no room for a Christmas tree, I’ve pulled out a decently tasteful faux-pine garland, which I string along my ceiling beams and adorn with colorful, sparkly things.

Although I love the look of blown glass decorations in their many trompe-l’oeil iterations, I prefer decorations that won’t shatter. I’m too attached to shiny objects to accept the possibility that they might break. Therefore, I opt for paper garlands, multicolored ribbons, felt and beads. Over the years, I’ve watercolored, embroidered, and scotch-taped a variety of decorations, including a suite of Nutcracker-themed ornaments (from paper garlands of toy soldiers to a felt Clara ballerina tree-topper).

But recently, my obsession has been pressed tin, and I have wreathed my winter nights with crafting sheets of metal into ornaments.

The more ornaments I made, the more ideas I had. One pomegranate turned into a full orchard of fruit. A swan turned into a winged menagerie. A coupe of champagne turned into a New Year’s feast. Requests from my mom and ideas for gifts turned into a Welsh dragon and a grandfather clock.

I will continue to make ornaments throughout this Christmas season—and for many years to come—but I thought I would share this first batch now that almost thirty are out of the oven!

Templates

I sketched out templates for my ornaments on paper, and traced them onto the metal sheets using a wooden tool. If you’d like to replicate any of my ornaments, feel free to download and print these!

In order to replicate the craft, all you need are craft metal sheets (like these from Cultura or these from Blick) and wooden embossing tools (like these). Alternatively, a dull pencil or the back of a paintbrush will do! It’s easier to press into the metal on a surface that has some give, such as felt or cardboard.

An imperfect history of tin Christmas ornaments

A 2003 Martha Stewart Living article about punched tin ornaments seems to have gone viral on the DIY-net. Consequently, my Instagram and Pinterest feeds have been full of punched and pushed metal ornaments.

This kindled a need to craft which burned through me like a bonfire on Guy Fawkes Night!

But pressed tin Christmas ornaments did not originate in early-2000s craft print journalism! Here, I propose something like a history of tin Christmas ornaments, which should be read more as a pseudo-researched moodboard…

As early as the late middle ages, artisans were crafting devotional designs on thin metal sheets with embossing and punching techniques. The Victoria and Albert Museum’s vast collection of decorative objects includes many examples of late medieval and early modern embossed and engraved bas-relief metal plaques. Mostly (though not always) depicting religious scenes, these adorned altars, chapels, and personal devotional spaces.

See footnotes for links to the V&A pages for each of these plaques.1

When the Industrial Revolution made tin more affordable for architectural embellishments2, tin Christmas decorations inspired by folk motifs also became popular in Central Europe.

The German Christmas Museum (Weihnachtsmuseum) in Rothenburg ob der Tauber provides an overview of decorations by material and spotlights pewter (a tin alloy). According to their article “All About the Christmas Tree,” pewter became popular during the affluent “Gründerzeit” era in the mid-19th century.3

Pewter ornaments are still handmade in Germany today: in a small workshop outside of Munich, the family-owned Wilhelm Schweizer firm still casts and paints pewter ornaments using 200-year old techniques!

In the Oaxaca region of Mexico in the 20th century, Spanish techniques blended with indigenous artistry originating in Precolumbian Mesoamerican metallurgy to create hojalata.4 Traditionally these objects depicted deities and sacred symbols, and although today they often depict Christian motifs. These devotional objects are generally known throughout Mexico as ex-votos or milagros, made of metal as well as wood or including small paintings.

The Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico has a great collection of tin folk art pieces, mostly dating from the 20th- and late 19th-centuries. Among these, many have a devotional purpose or depict Biblical scenes or characters.

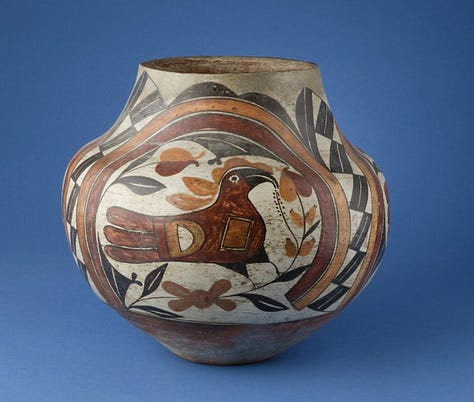

The pressed tin ornaments I most often see online these days also draw on motifs from Americana and Indigenous American art styles. They incorporate designs such as stars, hearts, animals, and other traditional symbols, often rendered in simplified or geometric shapes inspired by quilting, printmaking, ceramics, and other decorative arts.

Many of these don’t have a Christian connotation. Among works in metal, I found these two Americana weather vanes: one depicting the Roman goddess of the harvest, Ceres; the other depicting the Archangel Gabriel.

See footnotes for links to the references to each of these images.5

Eastern European and Scandinavian folk art is another frequent influence, with its bold colors, symmetrical patterns, and nature-inspired designs, such as Polish wycinanki, Ukrainian vytynanka, or Scandinavian paper cutout art.

See footnotes for links to references for each of these paper cutouts.6

And of course, many ornaments produced today simply reference contemporary objects or classic, Christmas motifs!

The practice of placing ornaments on an pine tree (or a plastic faux-branch…) has both pagan and Christian roots. The Norse Yule celebration, later merged with Christmas6, is thought to have involved burning a log for as many as 12 days. The Romans decorated their homes with greenery and candles for the New Year on January 1, following Saturnalia, celebrated from December 17 to 24. Christmas later “borrowed” the dates of this wildly popular pagan festival.7

As most of Europe became Christianized, evergreens retained symbolic weight. The main prop of a popular medieval play, Le Jeu d’Adam, was a “paradise tree” that represented the Garden of Eden.8

It wasn’t until the 16th century, however, that Renaissance-era German Christians began bringing whole trees inside their homes. Pious Lutherans set up a "paradise tree” in their homes on December 24, the feast day of Adam and Eve, and hung it with apples (representing the Garden of Eden), wafers (representing the Eucharist), and candles (representing Christ as the light of the world). In the same vein was the “Christmas pyramid,” triangular wooden shelves that held Christmas figurines: evergreens, candles, and a star. Eventually, the Christmas pyramid and the paradise tree merged into the Christmas tree.

By the 18th century, this tradition became more common throughout Germany. It spread to England in the 19th century thanks to Queen Victoria’s German-born husband, Prince Albert.

German immigrants had introduced the Christmas tree to North America in the 18th century, but it was British practices in the mid-19th century that cemented the tradition. The Victorian tree was decorated with toys and small gifts, candles and candies, popcorn strings, cakes hung by ribbons, and paper chains.

Victoria and Albert Museum Plaques

1 - Copper-gilt plaque of St Francis, Spain, sixteenth century.

2 - Plaque from a pax. Burgos, Spain, 1520.

3 - Plaque, made in Léon, Spain around 1530.

4 - Gilded copper alloy plaque depicting a love scene after an illustration designed by F. Boucher. Plaque signed and dated by 'P Suther', Paris, 1748.

5 - Plaque, copper, London, ca.1930-1932, probably made by A.F. Thompson

In North America, pressed tin was widely used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for ceiling tiles, cornices, and wall panels, particularly in Victorian and Edwardian architecture. Cheap, Quick, & Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials, 1870-1930 by Pamela Simpson.

Gründerzeit translates to “age of the founders.” This period lasted for six years (1867–1873) during which the economic rise of the German Empire created hundreds of new businesses, banks, and railways. It ended with a massive stock market crash in 1873.

Sarah Teel, research by Codee Ratliff. “Oaxacan Metal Folk Art,” Missouri State.

Americana and Native American art

1 - Heart-and-Hand Love Token, possibly Connecticut, ca. 1840–1860. Folk Art Museum.

2 - Independent Order of Odd Fellows Second Degree Banner, Cincinnati, ca. 1882–1900. Folk Art Museum.

3 - Star Finial, ca. 1875–1925. Folk Art Museum.

4 - Kenojuak Ashevak, Untitled, 2009. Dorset Fine Arts.

5 - Acoma jar, New Mexico, ca. 1895. Denver Art Museum.

6 - Coeur d'Alene flat bag, Idaho, ca. 1895–1905. Metropolitan Museum.

Weathervanes

1 - Iron weathervane in the form of Ceres, New England, mid- to late-19th century. Christie’s.

2 - Gould and Hazlett Company, Archangel Gabriel Weathervane, Boston, 1840. Folk Art Museum.

“According to the saga of King Haakon Haraldsson of Norway, who ruled in the 10th century, the Norse Yule celebration and Christian Christmas celebration were merged during his reign.” (Britanicca)

Many parallels have been drawn between Saturnalia and the Twelve Days of Christmas and the Feast of Fools.

Directions for the set from the script of Le Jeu d’Adam:

Let paradise be constructed in a prominently high place [constituatus paradisus loco eminentori]; let curtain and silken hangings be placed around it at such a height that those persons who will be in paradise can be seen from the shoulders upwards; let sweet-smelling flowers and foliage be planted; within let there be various trees, and fruits hanging on them, so that the place may seem as delightful as possible [ut amoenissimus locus videatur].